On The Record

Interview with Miki Hasegawa

A Voice For Herself And Others

己の声、他者の声

After publishing “Internal Notebook”, a brutally honest book about child abuse in Japan which has helped many to open up about their dark past, photographer Miki Hasegawa is now working hard to expand the conversation into another taboo subject — sexual crimes. She tells POY Asia Co-Director Kay-Chin Tay it is all about giving everyone a voice.

日本おける児童虐待についての残酷なまでに誠実な本である「Internal Notebook」を出版し、多くの人が暗い過去を打ち明けるきっかけとなった写真家、長谷川美祈は現在、もう一つのタブーである性犯罪に議論を展開しようと懸命に取り組んでいます。彼女はPOY Asia 共同ディレクターである郑家进に最も重要なのはすべての人に声を与えることだと語ります。

写真集「Internal Notebook」では、虐待を受けて育った人8人について写真やインタビューを通してその人生を視覚化している。

The photo book 'Internal Notebook' is about eight people who grew up in an abusive environment and visualised their lives through photographs and interviews.

Why did you start the project “Internal Notebook”? Was it due to your fear that you might abuse your young daughter? Can you tell us what was the source of your fear?

I’m not sure if this is the same as in other countries but at least in Japan, the expectation of women is to be a perfect role model and exemplar in a family. This is an unbreakable rule deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

My pregnancy was not a smooth one. I was at multiple risk of miscarriage and premature delivery. Even after giving birth, I was not able to breastfeed my daughter properly.

All these episodes added to my feeling that I am/was not a qualified mother, one who was not able to be the ‘perfect example’ that was expected of me. Because of my ‘flaws’, I was worried that I would become an abusive mother.

幼い娘さんを虐待してしまうのではないかという恐怖から、「Internal Notebook」を始めたそうですね。その恐怖心はどこから来ているのでしょうか?

他の国でもそうかもしれませんが、日本において、母親とはこうであるべきという規範、母性神話のようなものが根強くあります。私はそこからはみ出してしまうような、母親らしいことができない母親だったので、虐待してしまうかもしれないという恐怖心はそこから来ていたと思います。

私は、最初に妊娠中からつまずきました。切迫早産の危険があり、入退院を繰り返しました。出産後は母乳をうまく飲ませることができませんでした。母親としてできるべきことができないということを実感し、ダメな母親だと痛感しました。

橋本隆生は、虐待を受けていた当時に住んでいたアパートへ私を案内してくれた。

Ryusei Hashimoto showed me to the house where he used to live when he was being abused.

Were all the people you interviewed in the book very cooperative from the beginning?

Yes, they were very cooperative. At the beginning, we communicated by emails and text messages and after that, we met up in person. One of them showed me the place where he used to live when he was a child. Another person showed me the diary and shared some old pictures. I also showed them my dummy book in progress so that they can understand my intentions and that helped to convince them to collaborate with me. They also shared suggestions for the book and I learnt a lot from them.

この本で取り上げられた方々は、最初からとても協力的だったのですか?

そうですね。非常に協力的でした。最初はメールでやり取りをしましたが、直接会った日に、幼少期に暮らしていた場所へ案内をしてくれた方もいますし、日記や過去の写真などを持って来てくれた方もいました。実際に会い、話をし、制作中のダミーブックを見てもらうことで、私の意図を理解してくれて、より協力的に、そして様々な提案などをしてくれるようになっていったと思います。私自身、彼らから多くのことを教えてもらいました。

秋本 蓮は当時、自身の皮膚を強く掻きむしる自傷行為をしていた。

Ren Akimoto was self-harming by scratching her own skin hard back then.

Why do you think they agreed to speak with you?

Actually, when I first communicated with them by emails and text messages, they were not sure if they were able to help me with the project. Most of them had never shared or had the chance to share their experiences with anyone before. Even if they did have a chance to talk about it, they were not taken seriously. And I think it was because people said there was no ‘evidence’ of the abuses. And yet, I think they probably always had the desire in their hearts to talk about their experiences. After getting to know them better, I feel that as long as someone is willing to listen to them, I am sure they would have been ready to talk to others, if not me.

なぜ、被写体の方々は、あなたに語ってくれたのだと思いますか?

メールでやり取りをした際に、彼らは自分自身の話は何も役に立たないのではないか?ということを気にしていました。彼らが虐待を受けたという証拠は何もないからです。そして話をしてもきちんと聞いてもらえなかった経験があったのだと思います。それでも、おそらく彼らは自分の経験を話したいという気持ちがずっと心の中にあったのだと思います。だから、彼らの話を聴きたいという人が居たなら、きっと私ではなくても彼らには話す準備はできていたのだと思います。

秋本 蓮は、摂食障害やその他の精神疾患を発症していた。そして大量の薬を常に持ち歩いていた。

Ren Akimoto had suffered from eating disorders and other psychiatric problems. And she always had a large amount of medication with her.

How did you gain their trust to speak with you?

Frankly, I am not sure if I gained their full trust in the first place. Sometimes I wonder if I can be a trustworthy person or not. When working with them, there are several things that I always bear in mind and one of them is to always be transparent and honest with them.

For example, I would always make it a point to share the progress of the book with them, and to explain to them the purpose of using certain pictures and content from the interviews. Before releasing anything, I would always try to get their approval for what they shared with me, including their opinions and ideas. I also asked them to check the finished book and gave it to them. To me, this book is possible only with their support and with their close collaboration. So this book is by them, and for them. I really cherish the fact that we had made this together.

Even now, when the book is used in exhibitions or articles being extracted or cited, I will still ask for their permission in case there are pictures or words or scenarios that they prefer not to be public now. I don’t want them to have any bad feelings about it after the book is published. While a published photo book cannot be changed, there are other opportunities for exposure, such as exhibitions, and I want to reflect their thoughts at that moment in time.

I hope that if I continue with this practice of consulting them, they will continue to trust me.

どのようにして彼らの信頼を得たのでしょうか?

信頼を得ることができたかはわかりません。そもそも私は、信頼に足る人間ではないかもしれないので… 心がけていることはあります。

途中経過のダミーブックを見せに行き、どのように、どの写真を使用するか、なぜその写真を使うのか、インタビュー内容の文章など、その都度、確認をしてもらったり、意見やアイディアを教えてもらっていました。もちろん完成本も確認してもらい、本人にお渡しもしています。 現在も、展示や記事などで掲載される場合も、写真の使用について毎回彼らに連絡を取って、了承を得ています。

彼らのおかげで出来た写真集なので、共に作ったということを大切にしているのと、彼らが嫌な思いをするものにはしたくなかったです。写真集は変更することはできないですが、それ以外の展示など露出する機会には彼らのその時点での思いを反映しています。彼らが使用されたくない写真や言葉があれば、使用しない選択もしています。そうした姿勢をし続けることが信頼へと結びついていけたらいいなと思っています。

山田 可南は、自身が受けた親からのネグレクト、再婚後の父による性虐待などに向き合いながら子どもを育てている。現在も適切に子ども達を育てることができるように様々な努力をしている。

Kanan Yamada is raising her children while facing the neglect she suffered from her own parents and sexual abuse by her stepfather. She is still making various efforts to ensure that her children are properly raised.

You even managed to get the abusive parents to be featured, do you think they are truly remorseful?

Many of the parents involved still do not think they had been abusive or had abused their children. A lot of them denied any wrongdoings. The parents believe that discipline is necessary and for the good of their future, so they do not consider their actions abusive at all and are sadly not remorseful.

However, some of them did regret and have apologized to the children.

In the book, one of the victims met the father after many years and the father apologized to the child who was abused who is now a grown up. In another case, there is a woman who was abused in her childhood and is now married and has become a mother. She also started hitting her children. She is still suffering and learning and seeking how she can properly raise her children.

あなたは、その加害者たちを取り上げることにまで至りましたが、彼らが本当に悔いていると思いますか?

彼らの加害者である両親たちは、多くは虐待したと思っていないと聞いています。本人たちは否定しているそうです。子どもの将来を考えての「しつけ」だと思っているのです。「しつけ」なので、悔いるよりは、良いことをしていたと考えている親も多くいると思われます。

なかには、悔いている人もいます。ずっと縁を切っていた父に会い、謝罪された人もいますし、また、幼少期に虐待を受けて育ち、その後、母親になって子どもに手をあげてしまった女性が登場しますが、彼女は現在も苦しみながらも、どうしたら適切に子どもたちを育てることができるかを勉強し、模索しています。

東京のReminders Photography Strongholdで行われた写真集制作ワークショップでは、ギャラリーキュレーターの後藤由美さん、オランダ人ブックデザイナーのTeun van der HeijdenさんとSandra van der Doelenさんと一緒に制作することができました。

The photo book making workshop held at Reminders Photography Stronghold in Tokyo, where I had a chance to work with the gallery curator Yumi Goto and Dutch book designers Teun van der Heijden and Sandra van der Doelen.

The first batch of “Internal Notebook” was handmade. Can you tell us about your process?

Firstly I attended a photo book making workshop held at Reminders Photography Stronghold in Tokyo, where I met the gallery curator Yumi Goto and Dutch book designers Teun van der Heijden and Sandra van der Doelen, who were instructors for a workshop on making photo books.

Based on ideas obtained from the workshop, I continued consulting Yumi Goto for the editing, composition, selection of paper, binding method, cover design etc. We went through repeated trials and errors to refine and complete the book.

Making the photo book by hand has the advantage of allowing me the freedom to create the photo book I want. But more than that, I feel that the process of making the book is a very important time for me. At first, I edited the book by pasting photos onto a plain piece of copy paper, and at that point, I started to realize which images are missing or necessary to tell the story. By repeating such a process, I can create while constantly asking myself the important questions such as: ‘why do I have to tell this story?’, ‘why this photo?’, ‘why this edit?’.

「Internal Notebook」の最初の出版物は手作りでした。そのプロセスについて教えてください。

最初に、東京のギャラリーであるReminders Photography Strongholdで行われた写真集制作ワークショップに参加しました。ギャラリーのキュレーターである、後藤由美さんと、オランダのブックデザイナー、トゥーン・ファン・デル・ハイデン、サンドラ・ファン・デル・ドゥーレンが講師となり、写真集制作をしました。その際に得たアイディアなどを元に、その後、後藤由美さんとのコンサルティングを繰り返しながら、編集や構成、紙の選択、綴じる方法、表紙のデザイン、などトライ&エラーを繰り返しながら推敲して完成へと進みました。

写真集を手で作ることによって、自分の思う写真集が自由に作ることができるという利点はありますが、それよりも私は制作している過程がとても重要な時間になっていると感じています。最初は、なんでもないコピー用紙に、写真を貼りながら編集をするのですが、その時点で、ストーリーを伝えるためには足りないイメージや、必要なイメージがわかってきます。そうした作業を繰り返すことで、「なぜこのストーリーを伝えなければならないのか」「なぜこの写真なのか」「なぜこの編集なのか」という一つ一つの「なぜ」に向き合いながら作っていくことができるのです。

「Internal Notebook」の最初の制作販売は手作りで行われ、普及版がイタリアの出版社のCeiba Editionsより刊行された。

The first batch of "Internal Notebook" was handmade and the first mass-produced version was published by Italian publisher Ceiba Editions

Do you think your book has made any positive impact?

Honestly I cannot really comment on this but in Japan, the book has been featured on TV and newspaper and we had several exhibitions around Japan. During the exhibitions, I had opportunities to give talks and participate in dialogue sessions with subjects in the book. I hope this is a start of the movement to think about the social issue in Japan regarding abuse.

One of the positive changes that came out of this project is that at one of the exhibitions, three people who contributed to the book met and they formed a group to share about the abuses with others in their own words.

Although their activities are currently suspended due to the effects of the coronavirus, I believe that the activity itself gave them the strength to live, as well as the importance of letting others know that they had been victims of abuse, and that it gave them the power to express their thoughts and experiences to others who had also been victims. I think it gave them the strength to express their own feelings and experiences of victimization.”

あなたの本が、良い変化をもたらしたと思いますか?

正直、分からないですが。ありがたいことに、日本でもテレビや新聞などに取り上げて頂いたり、各地で展示などもさせて頂きました。展示の際は、講演をしたり、共に対話する時間を設けたりしたので、虐待について考える機会になれていたらいいなと思います。

写真集に参加してくれた3名が展示会場で出会い、自身たちの言葉で虐待について発信していくグループを作り活動をしたことが私のなかでは良い変化のひとつです。コロナの影響もあり、現在は彼らの活動は休止していますが、それでも、虐待の被害を受けたことを当事者が発信する重要さとともに、その活動自体が、彼らの生きる力にもなったでしょうし、同じように被害を受けた人たちへも自身の思いや被害経験を表現していいのだと思える力になったのではないかと思います。

虐待を受け、保護された後、児童擁護施設で育った菊池清子は、遊園地などの親子の声からフラッシュバックを起こしてしまうことがあると語った。

Kiyoko Kikuchi, who was abused and raised in a children's shelter, said she sometimes has flashbacks from the voices of parents and children at amusement parks etc.

To do the kind of social project, you also need to be very open about your own experiences. Do you find it difficult to share your own trauma?

I don’t know if I have been truly able to fully grasp my own trauma, but I don’t mind talking about it so perhaps that’s why it wasn’t difficult to discuss. I also think it is because there was someone in my life who would listen to me. It is very important to have someone who listens, and not deny or reject us. If someone doesn’t have that kind of support, it can be very difficult to share the trauma and they may feel fear, anxiety and will need courage to discuss it in the future.

このような誠実な仕事をするためには、あなた自身の経験についても非常に誠実である必要があります。ご自身のトラウマを共有することは困難だと思いますか?

私自身の経験がトラウマになっているかというと分からないですが、私は自分の経験を語ることが嫌ではないので、困難ではなかったです。でもそれはおそらく、今まで生きてきたなかで、自分の話を聴いてくれた人がいた経験があるからなのだと思います。聴いてくれた、否定されなかった経験があるということは、非常に大切だと思います。その経験がない、または乏しい場合、トラウマを共有することは、非常に困難で、不安や恐怖もあるでしょうし、勇気が必要になってしまうと思います。

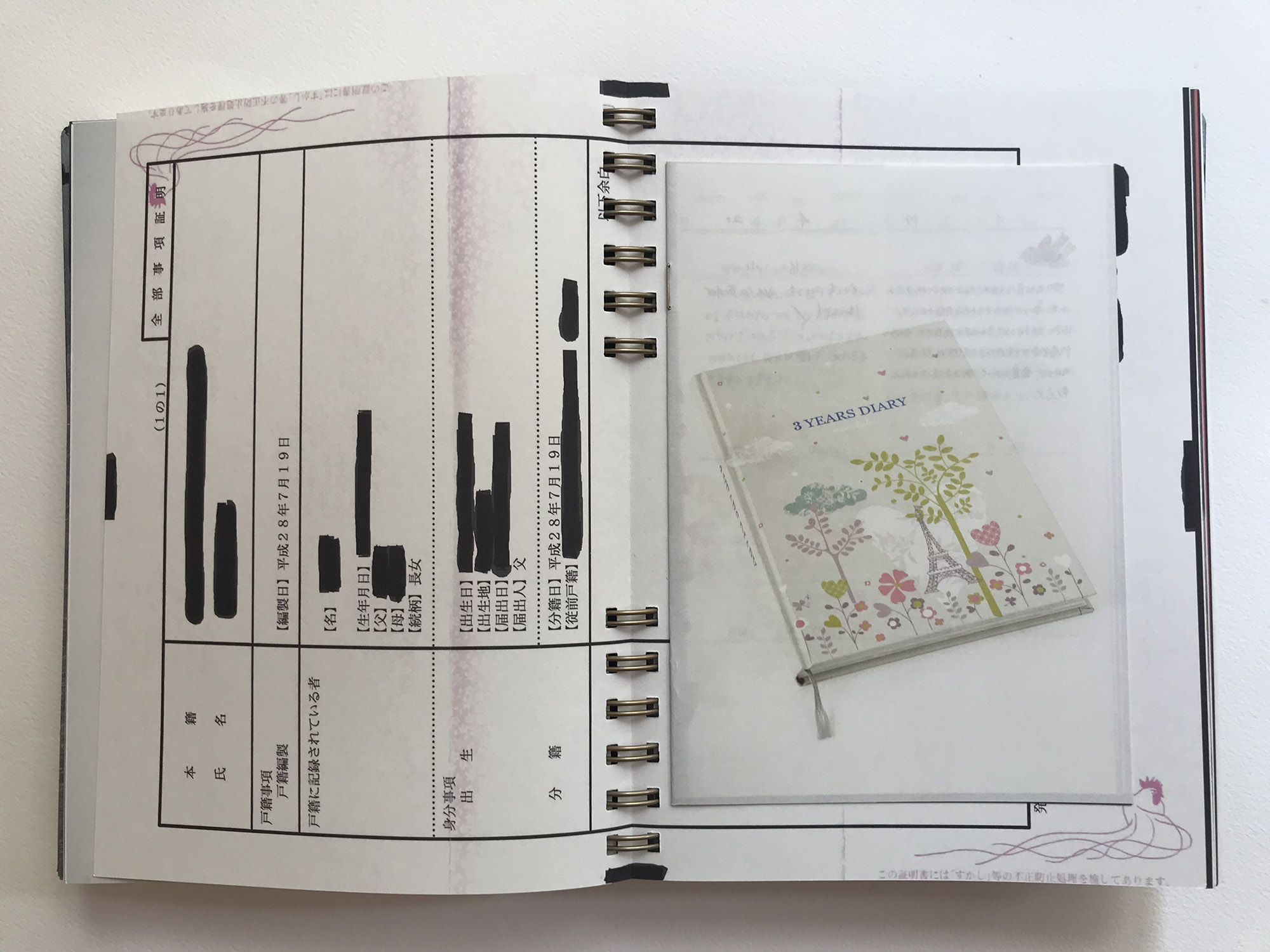

秋本 蓮は、虐待をした親と縁を切りたいために分籍の申請をした。分籍しても実際には法的な効力はないが、それでも彼女は気持ちが楽になったと語っていた。彼女の心の声である日記帳とともに編集されている。

Ren Akimoto applied for a removal herself from her abusive family. Although the removal has no actual legal binding, she said she still felt better. It is edited together with her diary, which is the voice of her heart.

How do you fund your projects? Are you a full-time documentary photographer?

I’m a freelance photographer who shoots for magazines, websites, and news outlets. I use the income from my freelance jobs to fund my projects.

プロジェクトの資金はどのように調達しているのですか?あなたは、フルタイムのドキュメンタリー写真家なのですか?

私はフルタイムの写真家ではないですが、フリーの写真家として、雑誌や、webニュースなどから撮影の依頼を貰って仕事をしています。そうした報酬からプロジェクトの資金を捻出しています

Your next book is about sexual abuses. How did that come about?

While I was researching for “Internal Notebook”, I met some people from a self-help support group for sexual victims and I had a chance to join some of their meetings. Also, some of the people appearing in the “Internal Notebook” have also been sexually abused.

Sexual abuse is actually very common in child abuse. However, it is not well known. In addition, it is not uncommon in Japanese society to be sexually abused not only by parents. The #metoo movement has allowed people to communicate about the problem, but many continue to remain silent and they will be criticized or targeted and get even more hurt when they do speak out. I am one of the people who make up such a society, and it made me consider whether the words I have said, the actions I have taken and the fact that I have done nothing in my own life have also been elements in creating a society that condones sexual assault.

次の本は性的虐待について書かれていますね。これはどのようにして生まれたのでしょうか?

「Internal Notebook」の制作時にリサーチするなかで出会った方々が、性被害者の自助グループを開催していて、何度か参加させて頂いた縁から生まれました。「Internal Notebook」に登場する方々のなかにも性虐待を受けた人もいるように、子どもの虐待において性虐待は実は非常に多いです。しかし、それはなかなか知られていません。また、親からだけでなく、生きていくなかで性被害に遭うことは日本社会において少なくはありません。#metoo運動などで性被害を受けた当事者の方々が発信をできるようになったように見えていますが、実際には、多くの方々は沈黙し続けていますし、発信しても傷つくようなバッシングを受けることも多いです。私は、そうした社会を構成している1人であり、私自身が生きてきたなかで、発した言葉や、行動、何もしなかったということも性加害を容認するような社会を作り出す要素になっていたのではないかと考えさせられました。

現在進行中の性暴力に関するプロジェクトのダミーブック。性犯罪加害者へ性犯罪再犯防止プログラムを行なっているクリニックに取材を行っている。

A dummy book of ongoing projects on sexual violence. The project is interviewing clinics that run sexual offence re-offending prevention programmes for sexual perpetrators.

Are you planning to use the same approach in “Internal Notebook” with your current project?

This time I might change my style a little, but I don’t know what that will be yet.

What I had been thinking about lately is the importance of using visualization to depict the victims and their pain, but I also ask myself why should the victim be the ones to send the messages? Why are the victims always the ones to get exposed?

I fear that even if they transmit their messages at their own wish, if the recipient does not have the knowledge and the mature background to receive their messages, they will just end up being sensationalised and consumed. So, I think this time, we need to discuss, talk, and focus on the perpetrators first.

In the case of sexual violence in Japan, thanks to the #metoo movement and others, there are now very many more opportunities for victims to come forward and talk about their own victimisation.

But there are also many second rape statements that blame the victim after hearing the victim’s words. In other words, the atmosphere for accepting victims’ words is still immature.

In addition, the media (including myself) that take up and disseminate the victims’ stories only exaggerate the sensational words of the victims and so on, consuming them and ending up with the attention.

In such a situation, the perpetrators are not always mentioned or photographed.

Essentially, victims are created because there are perpetrators, so I have come to believe that if we really want to create a society without sexual violence, we should first talk about the perpetrators.

I believe that unless we first know who the perpetrators are and how they lead to perpetration, and unless society does not give birth to perpetrators, the damage will not disappear either.

次のプロジェクトでも同じようなことをする予定ですか?

今回は、少し、自分のスタイルを変えたいと思っています。が、どうなるかまだわかりません。

ここ最近考えているのは、被害に遭った当事者の方の言葉や彼らの傷みを視覚化することはとても重要なことなのですが、なぜ、いつも被害者側から発信しなければならないのか?なぜ、被害者が視覚化されなければならないのか?という疑問があります。本人たちの希望で発信したとしても、受け取り側が彼らの発信を受け取ることができるような知識を持ち、成熟した土壌が整っていなければ、ただ、センセーショナルに扱われ、消費されて終わってしまうのではないかという懸念を感じています。

まずは、加害者について学び、語り、視覚化を試みる必要があるのではないかと考えています。

日本の性暴力の場合、#metoo運動などのおかげで、被害者が名乗り出て自分の被害について話す機会が非常に多くなりました。

しかし、被害者の言葉を聞いてから被害者を責めるセカンドレイプ発言も多くなっています。つまり、被害者の言葉を受け入れる土壌がまだ未熟なのです。

また、被害者の話を取り上げて発信するメディア(私も含めて)は、被害者のセンセーショナルな言葉などを誇張して消費し、注目されることに終始するだけです。

そんな中で、加害者について語られたり、視覚化されることはほとんどないです。

本来、加害者がいるから被害者が生まれるのだから、本当に性暴力のない社会にしたいと思うならば、加害者について語るべきだと思うようになりました。

加害者が誰で、どのように加害に至るのかを知り、社会が加害者を生まないようにしなければ、被害もなくならないと考えています。

雨宮ちふゆは、子どもの頃の親によるネグレクトにより、人格が複数できてしまった。彼女のノートには、人格によって違う筆跡の文字が並んでいた。

Chifuyu Amamiya has suffered from neglect by her parents in childhood, which has developed multiple personalities. Her notebook was filled with different handwriting for each personality.

Is your husband proud and supportive of what you do?

I think my husband doesn’t understand my job very well. I don’t mean it in a bad way, but he doesn’t interfere much, so it’s easy for me to do my job. When I need support, I know I can count on him. When I was away from home for a long period of time, he took care of the children, helped with the housework, and even helped me set up an exhibition.

あなたの夫は、あなたがしていることを誇りに思い、支持してくれていますか?

私の夫は、私の仕事をあまり理解していないと思います。悪い意味ではなく、あまり干渉をして来ないので私は仕事がやりやすいです。干渉はしないけれど、必要な時にサポートはしてくれます。長期間、家を空ける時は、子どもの面倒を見てくれたり、家事もしてくれますし、展示の設営を手伝ってくれたこともありました。

2017年11月に東京のReminders Photography Stronghold Galleryにて写真展「Internal Notebook」が開催された。この展示は、会場のある東京都墨田区の協賛を受け、虐待防止の講演会なども行い、多くの人々の関心を得ることができた。

In November 2017, the photography exhibition "Internal Notebook" was held at Reminders Photography Stronghold Gallery in Tokyo. The exhibition was co-sponsored by Sumida Ward, Tokyo, where the venue is located, and included a lecture on abuse prevention, which attracted a large number of people.

How are your projects perceived in Japan, as it is generally considered a conservative society?

At first the project was often featured or introduced overseas. I believe that by not showing my exhibitions in galleries in Japan, but rather at local centres where the public can easily visit, I have been able to gradually attract attention to my work.

However, people often perceive me only as a photographer who is focused on the difficult subject of abuse, and there is little focus on the social issue of child abuse. I felt that this project should have been an opportunity to learn and think about what everyone can do and see it more as a social problem instead of an individual problem.

I have been asked many times by people who visited the exhibition “Is this a true story?” I felt that the Japan government is beginning to discuss and address the social issue of child abuse more openly. However I thought that many people might still think that it is rare for parents to abuse their children, and that it is something that strange people do who are different from them.

日本では、まだとても 保守的な社会と思われていますが、あなたのプロジェクトはどのように受け止められていますか?

最初は、このプロジェクトは、海外で取り上げられたり、紹介されることが多かったです。日本での展示をギャラリーにこだわらず、一般の方々が訪れやすい地域のセンターなどでするようにしたことで、少しずつ注目を集めることはできたと思います。とはいえ「虐待という取り上げにくいテーマを撮影した写真家」という受け止められ方が多く、本来は、虐待についてより知ろうとしたり、個人の問題ではなく社会の問題として1人1人が何ができるかを考えるような機会のひとつにこのプロジェクトがなるようにしなければいけないと感じています。

展示を偶然目にした方からは、「これは本当の話なの?」と聞かれたことが何度かあります。

日本でも、子どもの虐待へ行政も取り組んだり、報道されたり、議論されたりするようになってきているように感じていましたが、それでもまだ、親が子どもを虐待するいうことは稀で、自分たちとは違うおかしな人がすることだと多くの人々は考えているのかもしれないと思いました。

現在進行中のプロジェクトの途中経過をReminders Photography Stronghold 京都分室Paperolesで展示した。

The ongoing project in progress was exhibited at Reminders Photography Stronghold Kyoto Paperoles.

Can you tell us about the current state of documentary photography in Japan? How is that compared to other parts of the world?

Japan has many documentary photographers who are producing many great projects. However I feel that there is a lack of opportunities and avenues to showcase their work in Japan.

There are many awards in other parts of the world, Pictures of the Year(POY) is one of them but in Japan, there are very few awards for documentary photographers and these Japanese awards are not open to international participants and there are often age limits. There are also restrictions that projects that had already received awards elsewhere cannot participate in Japanese contests, and the judges are always the same people.

I feel that the methods of expression in documentary photography have become extremely diverse around the world. And I can see that there are a lot of discussions about the method of expression, and I think that such things are encouraging photographers and giving rise to changes and turning points in the way they think about creating works. I feel that such critical viewing of photographs and dialogues with them are very rare in Japan. In addition, funds are necessary to proceed with the project, but there are not many grants. I feel that photographers themselves must take action to overcome such problems.

日本のドキュメンタリー写真の現状についてお聞かせください。世界の他の地域と比べてどうなのでしょうか?

私自身、まだまだ勉強中の身ですが…

日本には多くの素晴らしいプロジェクトを進行し、制作しているドキュメンタリー写真家がいると思います。しかし、そのアウトプット先が、国内ではあまりにも少なく、また広がりがないように感じています。世界の他地域では、多くのアワードもありますが、(Pictures of the Year もその一つだと思います。)日本国内でそうしたアワードは非常に少ないですし、またあっても、世界へは開かれておらず、日本国内のみだったり、応募するために年齢制限があったり、他で賞をもらっていない、他のアワードへ応募していない作品という制限もあったりします。審査員もいつも同じような顔ぶれです。

世界では、ドキュメンタリー写真の表現方法も非常に多様になっていると感じます。そしてその表現方法についても多くの議論が生まれている様子が見られていて、そうしたことが、写真家を育てるし、作品を制作する上での考え方にも変化や転機を生んでいると思います。批評的に写真を見ること、対話することがあまりにも日本では少ないと感じています。

またプロジェクトを進行する上で資金は必要になってきますが、助成金などもあまりありません。このような問題を写真家自身も打開するべく何か行動を起こさなければいけないと感じています。

神谷 芽未は、子どもの頃に母親から突きつけられた包丁を持参してくれた。彼女は結婚、出産で家を出たが、夫によるDVで再び、虐待をした母親の元で暮らしていた。

Megumi Kamiya brought a kitchen knife that was put to her by her mother when she was a child. She had left home to marry and have a baby, but again due to domestic violence by her husband, she lived with her abusive mother.

Do you have any advice for other documentary photographers who want to do similar works?

In the case of projects that cannot proceed without the cooperation of people involved, I think we always have to remind ourselves that shooting the photographs and publishing them as a work of art is a kind of ‘violent’ act and may hurt the parties with whom we cooperate.

If it still makes sense to do it, it is important to do it with utmost sincerity and perfectly, no matter how many years this will take, it is our responsibility as documentary photographer to complete these projects to the end, to continue to convey the thoughts of those who cooperated with us.

また、似たような作品を撮りたい他のドキュメンタリー写真家へのアドバイスがあればお願いします。

アドバイスというようなことは言えないですが。自分ではない当事者の方の協力無しには進められないプロジェクトの場合、撮影すること、作品として発表することは、ある種の暴力的な行為であり、協力者を傷つけるかもしれないということをいつも念頭に置いていなければいけないと思っています。それでも行う意味がある場合は、最大限、誠実に、そして完成させることが重要だと思います。何年かかったとしても、最後まで完成し、協力してくれた方々の思いを伝え続けることが、こうしたプロジェクトをする責任だと考えています。